Unveiling The Iran Chador: A Tapestry Of Culture, History, And Identity

Step into the captivating world of the Iran chador, a garment that transcends mere fashion to embody a profound cultural legacy and timeless elegance. Far more than just a piece of cloth, the Iran chador stands as a powerful symbol of identity, resilience, and spiritual connection within the rich cultural mosaic of Iran. It is a garment steeped in history, reflecting centuries of tradition while simultaneously being at the heart of contemporary discussions about personal freedom and societal norms.

This comprehensive exploration delves deep into the multifaceted nature of the Iran chador, from its physical characteristics and historical evolution to its modern significance and the ongoing debates surrounding its use. We will uncover how this iconic attire has adapted through political and cultural shifts, serving as a mirror to the nation's journey and the individual choices of its women. Understanding the Iran chador requires a nuanced perspective, acknowledging its diverse interpretations and the deeply personal meanings it holds for millions.

Table of Contents

- The Iran Chador: An Iconic Garment Defined

- A Journey Through Time: Historical Roots of the Chador

- The Chador in Modern Iran: Political and Cultural Shifts of the 20th Century

- Beyond Uniformity: Diversity in the Iran Chador

- Cultural Legacy and Spiritual Identity

- The Chador and Contemporary Debates in Iran

- The Global Context: Chador Beyond Iran

- Understanding the Iran Chador: A Call for Nuance

The Iran Chador: An Iconic Garment Defined

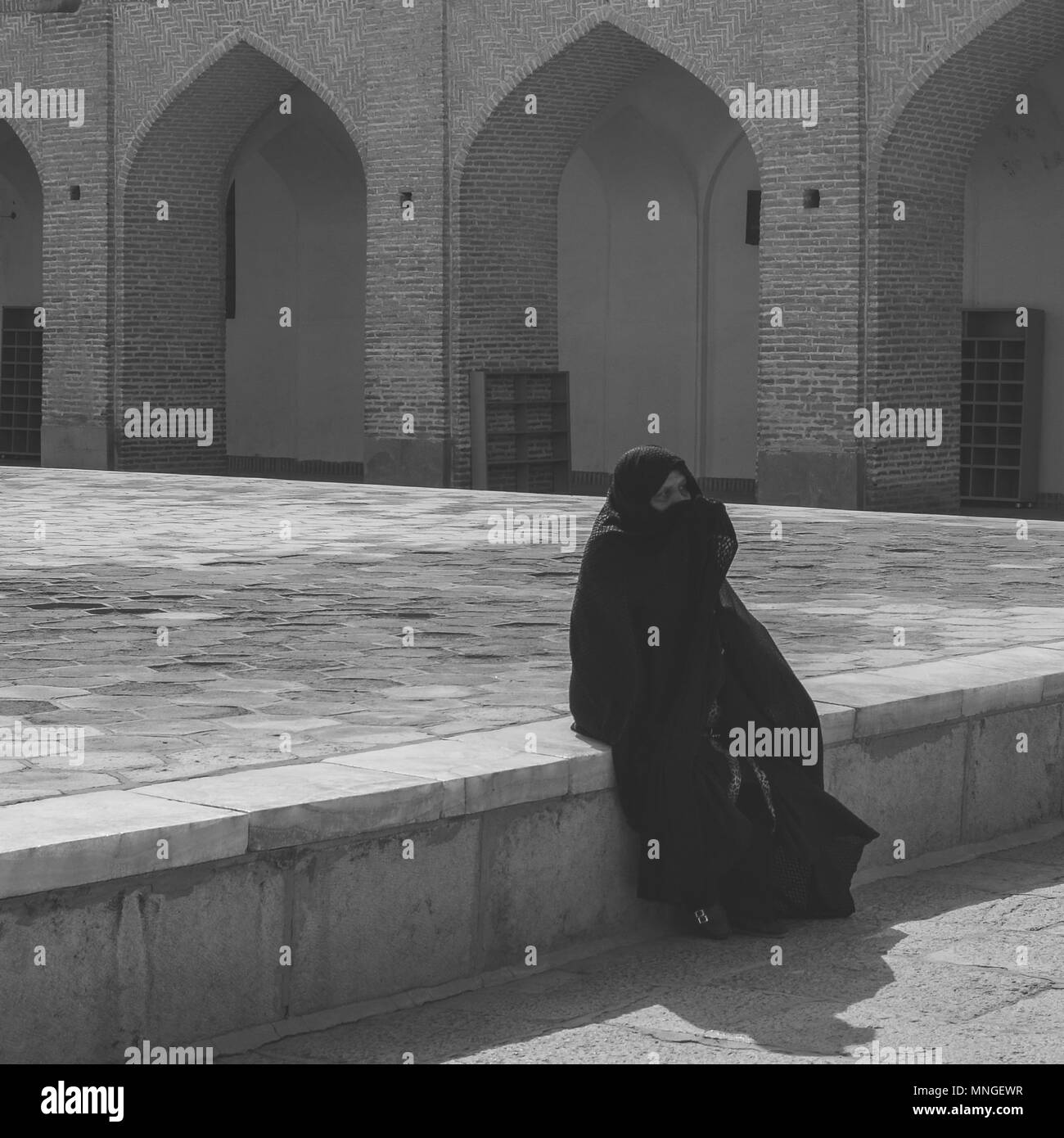

The Iran chador is perhaps the most iconic garment worn by women in Iran, instantly recognizable for its distinctive silhouette. Described simply, a chador is a semi-circle of fabric that covers the entire body and is open at the front. The garment is passed over the head, and the user maintains it closed at the front, often by holding it with one hand or by tucking it under the arms. Crucially, the chador does not have hand openings, buttons, or closures, differentiating it from many other types of outer garments. This traditional Islamic garment is characterized by its simplicity, with no stitching other than finishing stitches on the edges.

The materials used for the chador can vary significantly. It is often made of plain or patterned fabric, depending on the occasion and personal preference. While traditionally black is common, especially for formal or religious settings, chadors can be found in a range of colors and patterns, particularly for daily use or in more rural areas. This adaptability in material and design highlights that the chador, despite its iconic status, is not a monolithic entity but rather a versatile garment that accommodates both practical needs and aesthetic choices.

A common question often arises: what is worn underneath the chador? The answer is a matter of personal taste and practical necessity. There are no strict rules dictating the attire beneath a chador. Some women choose to wear modest clothing under their chadors as an expression of piety and as a matter of personal taste, ensuring that their entire ensemble aligns with their spiritual beliefs. Conversely, in revolutionary Iran, for example, many women chafed against the requirement of the chador, wearing daring outfits underneath, where no one could see them. This dichotomy underscores the chador's complex role as both a symbol of public modesty and, for some, a private canvas for individual expression.

A Journey Through Time: Historical Roots of the Chador

To truly appreciate the Iran chador, one must delve into its rich historical context. Its roots stretch back far beyond the modern era, intertwining with ancient Persian traditions and the advent of Islam. Historically, veiling and covering practices existed in various forms in the region long before Islam, often associated with social status or protection from the elements. However, during the Islamic period, the chador merely represented one type of clothing adapted to comply with Islamic dress codes. It was worn by women of all social classes and was a symbol of modesty and respectability, reflecting societal norms and religious interpretations of the time.

- Who Is Harry Jowsey Dating

- Jane Seymour Spouse

- Nicole Lampson

- Christine Whigham

- Tim Burton Dating History

It is vital to understand that the chador has never had a uniform function, shape, stitching, size, or even color throughout its long history. Its evolution has been dynamic, influenced by regional customs, economic conditions, and prevailing social attitudes. Over time, particularly as Islamic identity became more central to Iranian culture, the chador became increasingly associated with Islam and evolved into an important symbol of religious identity for Iranian women. This transformation was not a sudden decree but a gradual process, reflecting the deep integration of religious values into the fabric of Iranian society.

The chador, therefore, is not a static artifact but a living garment that has adapted and transformed across centuries. Its historical journey is a testament to the resilience of Iranian culture, echoing the nation's deep history and its continuous dialogue between tradition and modernity. From its practical origins to its symbolic significance, the chador encapsulates a narrative of continuity and change, making it a compelling subject for cultural study.

The Chador in Modern Iran: Political and Cultural Shifts of the 20th Century

The modern significance of the Iran chador is deeply tied to the dramatic political and cultural shifts of the 20th century. This period witnessed intense debates and policies surrounding women's dress, transforming the chador from a traditional garment into a potent symbol of ideological struggle and national identity. These shifts highlight how clothing, particularly for women, can become a battleground for competing visions of society.

Reza Shah's Modernization and the Controversial Ban

One of the most pivotal moments in the chador's modern history occurred during Reza Shah Pahlavi’s rule in the 1930s. Driven by a fervent push for modernization, Reza Shah embarked on an ambitious program to secularize and westernize Iranian society, taking inspiration from reforms in Turkey. As part of this effort, a controversial banning of the chador in public spaces was implemented in 1936. This decree, known as *Kashf-e Hijab* (unveiling), aimed to integrate women into public life by removing what was perceived as a barrier to progress and equality.

The ban was enforced rigorously, often with police officers forcibly removing chadors from women in the streets. This policy was met with mixed reactions. While some segments of society, particularly educated urban elites, welcomed it as a step towards modernity and women's liberation, a significant portion of the population, especially in religious and traditional communities, viewed it as a profound violation of their cultural and religious values. For many, the chador was not merely a garment but an integral part of their identity and faith. The ban caused immense social upheaval, forcing many women to withdraw from public life rather than comply with the new regulations. This period left a lasting scar on the collective memory, creating deep divisions and resentment that would resurface decades later.

The Chador's Resurgence Post-Revolution

The pendulum swung dramatically in the opposite direction following the 1979 Islamic Revolution. The revolution brought with it a profound re-emphasis on Islamic values and identity, and the chador quickly became a central symbol of this new order. What was once banned was now encouraged, and soon, mandatory. The post-revolutionary government introduced strict dress codes, making the chador, or at least a form of modest Islamic dress (hijab), compulsory for all women in public spaces.

For many women who had participated in the revolution, the chador represented a return to authentic Iranian and Islamic values, a rejection of Western cultural imposition, and a symbol of resistance against the previous regime's secular policies. It became a powerful emblem of the revolution's ideals. However, for others, particularly those who had experienced the freedom of choice before the revolution or who held different interpretations of Islamic dress, the mandatory nature of the chador became a source of contention and a symbol of state control over individual liberties. This complex relationship between the chador, political power, and personal freedom continues to define its significance in contemporary Iran.

Beyond Uniformity: Diversity in the Iran Chador

Despite its iconic and often politicized image, it is crucial to recognize that the Iran chador is far from uniform. As the provided data states, the chador has never had a uniform function, shape, stitching, size, or even color. This inherent diversity challenges the simplistic notion that the chador is a monolithic garment, revealing a rich tapestry of regional variations, personal adaptations, and evolving styles.

Across Iran's diverse provinces, one can observe subtle yet significant differences in chador styles. In some regions, chadors might be tailored with specific pleats or a slightly different cut to accommodate local customs or climatic conditions. The fabric choice also varies widely; while urban centers might favor lighter, more elegant materials for formal chadors, rural areas might opt for more durable, practical fabrics. Even the way a chador is worn can differ, with some women preferring a tighter wrap, while others allow for a more flowing drape.

This diversity extends to color and pattern. While the black chador is prevalent in many urban areas and is often associated with religious piety and formality, especially in cities like Qom and Mashhad, women in other parts of Iran, particularly in rural or tribal communities, might wear chadors in vibrant colors or intricate patterns. These colorful chadors often reflect local textile traditions and serve as a form of cultural expression, challenging the stereotype of a uniformly black and somber garment. For example, some nomadic tribes incorporate their unique embroidery and colors into their chadors, making them distinct markers of their identity.

Furthermore, the chador's function itself is not uniform. While it serves as an outer garment for public modesty, it is also often worn for praying (namaz) or for specific religious ceremonies. Its adaptability means it can be a daily utility garment for some, a formal attire for others, and a symbol of profound religious commitment for many. This inherent lack of uniformity underscores the chador's organic evolution within Iranian society, shaped by individual choices, regional customs, and the ebb and flow of cultural trends, rather than being a static, imposed form.

Cultural Legacy and Spiritual Identity

Rooted deeply in Iranian tradition, the Iran chador carries a rich history of modesty, grace, and spiritual identity. For millions of Iranian women, the chador is not merely a legal requirement or a political symbol, but a deeply personal expression of their faith and cultural heritage. It represents a connection to centuries of tradition, a tangible link to their ancestors and the values they upheld.

The concept of modesty, or *hejab*, is central to Islamic teachings, and for many, the chador is seen as the most complete and authentic embodiment of this principle. Wearing the chador is often an act of devotion, a way to express reverence for God and to uphold religious values in public life. It provides a sense of spiritual protection and allows women to feel a deeper connection to their faith. This spiritual dimension is particularly evident when the chador is worn for praying (*namaz*), transforming it into a sacred garment that facilitates communion with the divine.

Beyond its religious significance, the chador also functions as a powerful symbol of cultural continuity and resilience. In the face of external pressures and internal transformations, traditional attire like the chador serves as a visible marker of Iranian identity. It echoes the resilience of a nation steeped in history, reminding its people of their unique heritage and their enduring cultural distinctiveness. In a world increasingly homogenized by global trends, the chador stands out as a proud declaration of Iranian cultural pride.

For many women, wearing the chador is a conscious choice, an affirmation of their identity that intertwines their personal beliefs with their cultural roots. It is a staple of modest fashion in Iran, offering a sense of dignity and respectability in public spaces. This voluntary adoption by a significant portion of the population highlights that while the chador has been subject to political mandates, its enduring presence is also a testament to its deep resonance within the hearts and minds of many Iranian women who choose to wear it as a symbol of their faith, grace, and cultural belonging.

The Chador and Contemporary Debates in Iran

The Iran chador, despite its deep historical and cultural roots, remains a subject of intense contemporary debate, both within Iran and internationally. These discussions often revolve around the tension between individual choice and state control, reflecting broader societal shifts and aspirations.

Personal Choice vs. State Mandate

One of the most persistent aspects of the debate concerns the mandatory nature of the chador, or at least the broader concept of compulsory hijab, in public spaces. While many Iranian women embrace the chador willingly as an expression of piety and personal identity, others, particularly younger generations and those with more secular leanings, chafe against the requirement. For these individuals, the chador becomes a symbol of restricted freedom and state interference in personal matters. The data mentions that in revolutionary Iran, for example, many women chafed against the requirement of the chador, wearing daring outfits underneath, where no one could see them. This act of private rebellion highlights the desire for personal autonomy even within a restrictive public sphere.

Conversely, for those who choose to wear modest clothing under their chadors as an expression of piety and as a matter of taste and personal conviction, the debate is often framed differently. They see the chador as an empowering choice that protects their modesty and allows them to navigate public spaces with dignity, free from unwanted attention. This divergence of perspectives underscores the complexity of the issue, where the same garment can represent liberation for some and oppression for others, depending on individual beliefs and experiences.

Recent Legislative Changes and Their Impact

The ongoing tension surrounding the chador and dress codes in Iran has recently manifested in significant legislative developments. Iran's parliament has just passed a controversial bill that would significantly increase prison terms and fines for women and girls who break its strict dress code. This move comes in the wake of widespread protests and a heightened public discourse on women's rights and freedoms.

The new legislation, if fully implemented, would represent a further tightening of controls over women's attire, potentially leading to more severe penalties for non-compliance. This has sparked renewed concern among human rights organizations and many within Iran who fear it will further erode personal freedoms and exacerbate social divisions. The implications of such laws extend beyond mere clothing, touching upon fundamental questions of human dignity, bodily autonomy, and the role of the state in personal lives. The ongoing resistance, often subtle but sometimes overt, from women who challenge these dress codes, demonstrates the enduring power of individual agency in the face of state mandates, keeping the chador at the forefront of Iran's social and political landscape.

The Global Context: Chador Beyond Iran

While the Iran chador is most prominently associated with Iran, it is important to acknowledge that similar garments are worn by women in other parts of the Middle East and Asia. The chador is an outer garment worn by women in some parts of the Middle East, particularly Iran and Iraq. Its presence also extends to other regions, such as Afghanistan, where "des tchadors à Hérat" (chadors in Herat) are observed, and in parts of Pakistan and India, where similar large sheets intended to be drawn over the body are common. This global distribution highlights a shared cultural and religious heritage that transcends national borders, even if the specific design and nomenclature vary.

It is crucial to distinguish the chador from other types of Islamic veils and outer garments, such as the abaya (common in the Arabian Peninsula), the burqa (seen in Afghanistan and parts of South Asia), or the niqab (face veil). While all serve the purpose of modesty, their designs, coverage, and cultural contexts differ. The chador, with its specific semi-circular shape, lack of closures, and method of being held closed, maintains its unique identity within this broader category of modest Islamic attire. Its specific form and cultural significance are deeply rooted in Persian traditions, even as the concept of a full-body covering resonates across various Muslim-majority societies.

Understanding the chador in its global context helps to appreciate its unique position within Iranian culture while also recognizing the broader patterns of modest dress in the Islamic world. It underscores that while the principles of modesty may be shared, their expression is incredibly diverse, shaped by local customs, historical trajectories, and individual interpretations.

Understanding the Iran Chador: A Call for Nuance

The journey through the history, symbolism, and contemporary debates surrounding the Iran chador reveals a garment of immense complexity. It is not simply a piece of cloth, but a living artifact that embodies centuries of cultural evolution, religious devotion, political struggle, and personal expression. To truly understand the chador is to move beyond simplistic stereotypes and embrace the multifaceted narratives it represents.

We have seen how the chador has transformed from a traditional symbol of modesty and respectability into a focal point of national identity and political contention. Its controversial banning in the 1930s and its subsequent mandatory enforcement after the 1979 revolution underscore its role as a battleground for competing visions of Iran's future. Yet, amidst these political currents, the chador has also remained a deeply personal choice for many women, a cherished symbol of their faith, grace, and connection to their heritage. The inherent diversity in its function, shape, and appearance further challenges any notion of a uniform or monolithic meaning.

The ongoing debates in Iran, particularly regarding recent legislative changes, highlight the continuing tension between state authority and individual autonomy. These discussions are not merely about clothing; they are about fundamental questions of freedom, identity, and the very fabric of Iranian society. By acknowledging the diverse perspectives—from those who embrace the chador as an act of piety to those who resist its compulsory nature—we can foster a more informed and empathetic understanding.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the Iran chador is a powerful and evocative symbol, deeply interwoven with the fabric of Iranian history, culture, and identity. From its ancient roots as a practical garment of modesty to its modern significance as a political and spiritual emblem, the chador tells a story of adaptation, resilience, and profound personal meaning. It is a testament to the enduring strength of Iranian traditions, even as it continues to be shaped by contemporary societal shifts and individual choices. The chador is not just a garment; it is a conversation, a statement, and a reflection of the rich, complex soul of Iran.

We hope this comprehensive exploration has provided you with a deeper, more nuanced understanding of the Iran chador. Its story is far from over, continuing to evolve with each passing generation. We invite you to share your thoughts and perspectives in the comments below. What aspects of the chador's history or symbolism resonate most with you? Your insights contribute to a richer, more informed dialogue. For more articles on cultural symbols and traditions, be sure to explore other pieces on our site.

- Alex Guarnaschelli Boyfriend

- Karen Fukuhara Dating

- Deshae Frost Age

- Nia Peeples Husband

- Meghann Fahy Age

Iran Before the Chador

Iran Before the Chador

Chador muslim iran Black and White Stock Photos & Images - Alamy